It may be difficult to believe now but once, long ago, aluminium was the darling of commodity markets! When I started my career as a commodity analyst in the early-2000s aluminium was king. At that time the European and North American aluminium producers had some of the highest market capitalisations amongst global mining companies.

China changed all that.

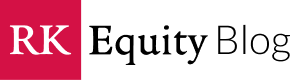

In the early 2000s, China was a net importer of aluminium. The China emergence finished all of that. As China started to develop it was investing in its own raw materials capacity, but its infrastructure was a shadow of what it is today. As a result there were large areas of stranded power in many regions and we saw China invest big into building its own aluminium smelting capacity to make use of that stranded power.

As a result, in only a few years China went from a mid-sized importer of aluminium and its products to a huge exporter of aluminium products. And, in the process, it killed off large amounts of the ex-China aluminium industry.

Plants in Europe (high energy costs, labour, alumina), the US (alumina, labour) and Australia (energy costs, labour) simply couldn’t compete with the huge volumes of material coming out of China.

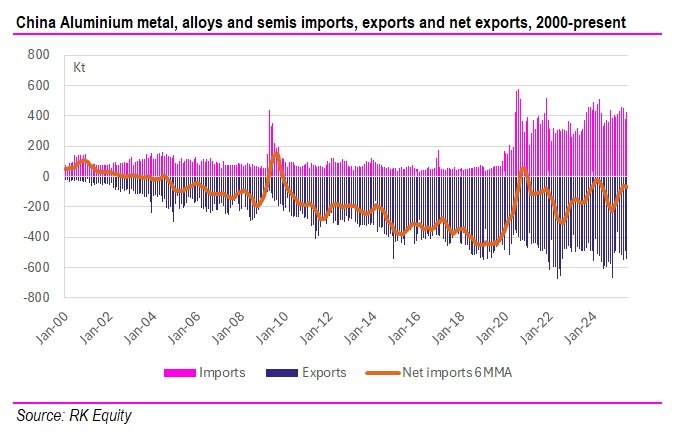

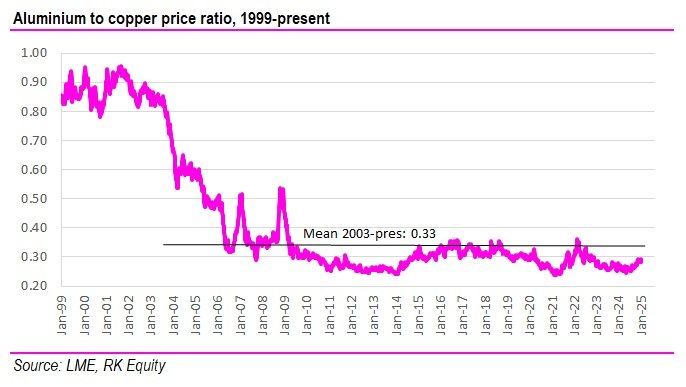

And, as a result of these exports, the aluminium price suffered. Don’t get me wrong – the aluminium prices has had its upcycles and downcycles, the same as any other commodity. But it lost a lot of ground to the other base metals. Over the past 22 years, the mean aluminium to copper ratio has been 0.33, and the mean aluminium to zinc ratio has been 0.95. Over the preceding five years, they were 0.86 and 1.55, showing the considerable amount of ground that aluminium has lost against other base metals over that period.

China’s trade behaviour is changing

But, having been a huge net exporter of aluminium and its products for most of the past 20 years, China’s behaviour is starting to change. China was not only an exporter of aluminium; it was an exporter of deflation.

By effectively dumping its aluminium manufactured with cheap, locally mined bauxite and low power costs, China was able to undercut most global aluminium producers.

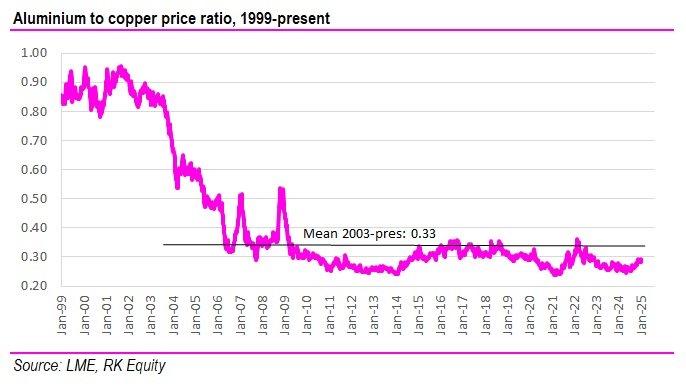

But, around 2020, China’s huge net export position started to decline. Don’t get me wrong; China is still a big exporter of semi-finished aluminium products, but China’s imports of aluminium metal and aluminium semis have increased substantially. And its imports of bauxite have also done so.

What I believe we’re seeing is a material structural change in China’s positioning within the global aluminium market and it has the potential to have the same magnitude of impact as China’s move to a net export position did in the mid-2000s.

From the chart above it’s possible to see that from mid-2020 onwards China started to import large amounts of aluminium metal and larger amounts of alloy and semi-finished products. This represented a major change in its trade balance compared to before that time.

The bulk of this imported material is coming from Russia (even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine) and, in the past 12-18 months, there is also an increasing amount coming from Indonesia, where a number of Chinese aluminium producers have set up shop.

China’s aluminium output is capped

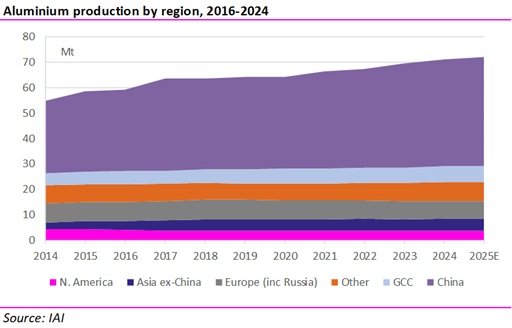

China has contributed c.42% of global primary aluminium supply growth over the past three years (and 83% over the past 10 years!), but in 2017 the Chinese government instituted a supply cap at 45Mtpa and, based on conversations with Chinese aluminium producers late last year, I understand that they intend to stick with that cap.

Given that production in China was c.43Mt last year, that suggests very limited growth. While there is some future output growth coming from the Gulf region and some from Indonesia, it’s likely insufficient to replace the magnitude of China’s growth over recent years.

Why has China capped its aluminium production? Well – a number of reasons.

If we think about what are the major raw materials for aluminium production, they’re alumina (bauxite) and power. China appears to have been conscious for a while that it is running its domestic reserves of bauxite down much faster than overseas reserves are running down and it’s put through a number of rules to control output of bauxite.

And, while there was considerable excess power available in China in the 2000s and early-2010s, that is certainly not the case any longer. China’s electricity demand is growing rapidly with its move towards EVs and we believe that China doesn’t want to effectively be exporting power by overproducing aluminium any longer. China has recently doubled down on this strategy by removing the VAT rebate on exports of aluminium products.

So the word has gone out to aluminium producers to produce enough for domestic consumption and no more. And that’s likely to have considerable impacts on global aluminium supply/demand balances.

But what about GCC and Indonesian supply?

Both of these regions are growing supply, but at nowhere near the growth rates that China has grown its supply at over the past 10-15 years. Indonesia is still a relatively small producer although it is expected to reach a capacity of 1.5Mtpa by the end of 2025 and 4Mtpa by the end of 2030. Indonesia benefits from abundant bauxite supplies and access to abundant (mostly Chinese capital). Its average industrial electricity price is US$0.07/kWh, which is about double those paid by Chinese smelters using HEP.

Capacity in the GCC region is much higher, with c.6.5Mtpa or 9-10% of global aluminium output. While it has been one of the fastest-growing production regions in recent years, issues around bauxite supply from Guinea have started to worry producers. Focus seems to be shifting to efficiency gains rather than wholesale capacity additions for now.

What about aluminium demand?

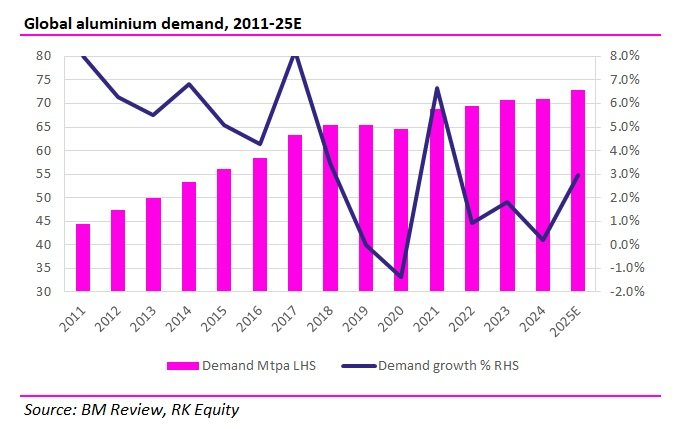

Global aluminium demand has grown at an average rate of 3.9% per annum over the past 15 years, although it has slowed considerably over the past five years due to the Pandemic and the slowdown in China’s property sector.

However, demand looks set to reaccelerate in coming years due to a number of key drivers:

- The rapid growth of electric vehicles which use large amounts of aluminium to substitute for steel to try and lower the weight of the vehicle.

- The rapid growth in solar installations on a global basis. Aluminium frames are used to support solar cells and modules.

- The substantial build out in power transmission infrastructure globally which will be needed to support the renewables build out and the shift to an electricity-rich demand structure.

- Substitution of copper in some consumer and infrastructure wiring applications due to a likely increase in prices.

Aluminium inventories at critical levels

So that’s the structural stuff, but what about what the market looks like now? Well, actually that’s kind of why I’m writing this because, in my view, the market’s already started reacting to the structural stuff, but investors aren’t really seeing it.

For most of the past 20 years of my career I’ve monitored exchange base metals inventories every Friday.

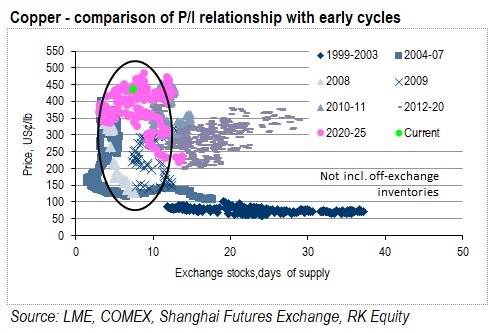

Over time there’s been a very strong – yet evolving – relationship between base metal prices and global exchange inventories. The chart below shows that relationship for LME copper vs global exchange inventories (stocks) on a days of supply (consumption) basis. For me as a commodities strategist it’s really important to look at inventories on a days of consumption basis rather than in absolute terms because there’s been a step-change in the magnitude of that consumption over the past 20 years.

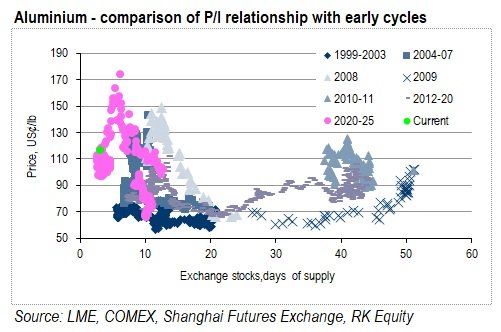

The chart above looks at the Price/Inventory (P/I) relationship for copper and this one below looks at the P/I relationship for aluminium. As you can see, I’ve split the P/I relationship over time because over different periods, the P/I relationship has been different.

Now, what jumps straight out for me from the charts above is that copper prices are at the top end of their recent range but copper inventories are nowhere near critical levels. In fact, they’ve been much, much lower in days of consumption terms than they are now.

But if you look at the aluminium chart, prices are well off their highs but inventories are at practically critical levels – they’re pretty close to the lowest level that they’ve ever been at in the 25+ years of data in my dataset.

Why aren’t investors reacting to the situation in Aluminium?

Well, plainly put – I think it’s because aluminium has been such a complete dog (that’s obviously the technical description!) for the past 20 years.

There have been many false dawns in aluminium over that time. I’ve never believed in any of them. But I believe in this one. Maybe because I have been a China watcher for 25 years and because I’m used to analysing what Chinese management teams do not say as well as what they do, but this genuinely does look to me like a structural change in behaviour from China.

And we’re seeing that with the collapse in inventory levels.

And it’s possible that China will start to deploy huge amounts of capital in Indonesia just as it’s done in nickel. But it will take time to identify new projects and it will take time to build them. And I think there’s an opportunity now in the global aluminium industry the like of which we haven’t seen for 20 odd years.

So what does this mean for the Al/Cu ratio?

So, first thing to point out is that I’m not “down” on copper by any stretch of the imagination. But I am really “up” on aluminium.

I think everyone knows that there’s a strong demand story in copper due to the development of the age of electricity. And I think everybody knows that copper supply is likely to grow at a slower rate than is going to be needed.

But I don’t think “everybody” realises that aluminium is actually in the same boat. And, indeed, the shortage has already started. And aluminium prices will need to increase substantially in order to justify investment in new supply from ex-China/Indonesia/GCC regions.

And that’s what I’m looking for. Will the aluminium/copper ratio return to the level that it was at in the early-2000s? It may, but that’s not my base case. But could it double from current levels? Triple even? I believe it could and should.

And, if it does that could have substantial ramifications for aluminium raw materials. But that’s a story for another day…